Was watching a pretty good Cormac McCarthy interview at Santa Fe Institute and he mentioned philosopher Otto Weininger, supposedly one of the greats. Austrian, grew up in a house of pianists. As for Cormac, I struggled through Blood Meridian but I like his life story, broke as shit, scraping syrup out a can. Smart guy, more math-science than arts and letters. Back to Weininger’s 1922 exposition—I don’t pretend to understand everything here, it’s okay, you don’t have to either. I think some of it can be appreciated at face value.

Some context which will aid your reading: Weininger is concerned with the conditions which would have to be fulfilled by a logically perfect language. “The essential business of language is to assert or deny facts. In practice, language is always more or less vague, so that what we assert is never quite precise.” From my understanding, he seems interested in the grey area between what we are capable of thinking and what we are capable of saying, and how this informs our life on Earth.

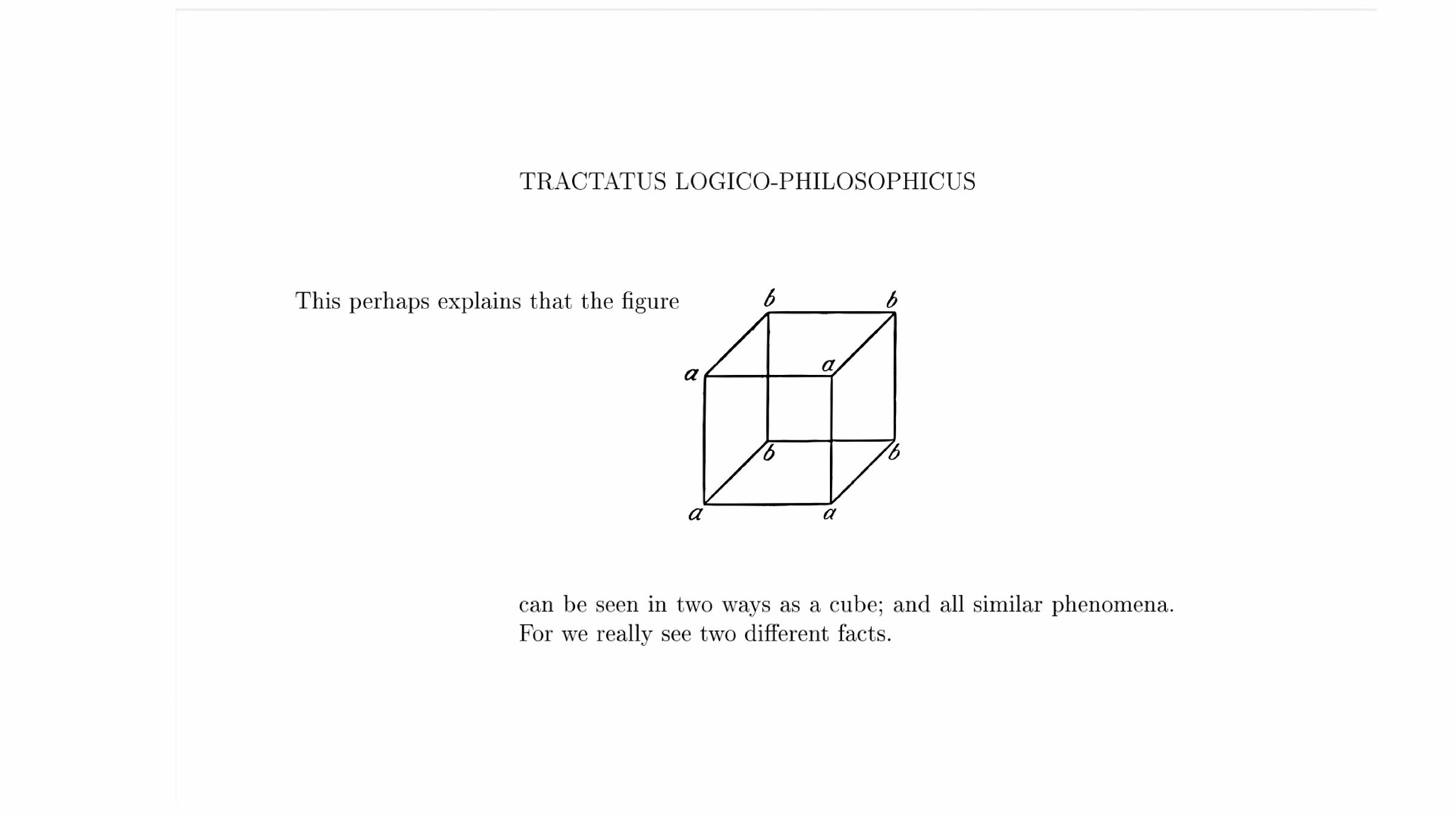

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

1. The world is everything that is the case.

1.21 Anyone can either be the case or not be the case, and everything else remain the same.

2.01231 In order to know an object, I must know not its external but all its internal qualities.

2.0131 A spatial object must lie in infinite space. (A point in space is a place for an argument.) A speck in a visual field need not be red, but it must have a colour; it has, so to speak, a colour space round it. A tone must have a pitch, the object of the sense of touch a hardness, etc.

2.014 Objects contain the possibility of all states of affairs.

2.022 It is clear that however different from the real one an imagined world may be, it must have something, a form, in common with the real world.

2.0232 Roughly speaking: objects are colourless.

2.02331 If a thing is not distinguished by anything, I cannot distinguish it—for otherwise it would be distinguished.

2.024 Substance is what exists independently of what is the case.

2.0251 Space, time and colour (colouredness) are forms of objects.

2.026 Only if there are objects can there be a fixed form of the world.

2.0271 The object is the fixed, the existent; the configuration is the changing, the variable.

2.033 The form is the possibility of the structure.

2.221 What the picture represents is its sense.

3.02 The thought contains the possibility of the state of affairs which it thinks. What is thinkable is also possible.

3.03 We cannot think anything unlogical, for otherwise we should have to think unlogically.

3.323 In the proposition “Green is green”—where the first word is a proper name and the last an adjective—these words have not merely different meanings but they are different symbols.

3.328 If a sign is not necessary then it is meaningless. That is the meaning of Occam's razor.

4.002 Man possesses the capacity of constructing languages, in which every sense can be expressed, without having an idea how and what each word means—just as one speaks without knowing how the single sounds are produced.

Language disguises the thought; so that from the external form of the clothes one cannot infer the form of the thought they clothe, because the external form of the clothes is constructed with quite another object than to let the form of the body be recognised.

4.024 One understands it if one understands its constituent parts.

4.112 Philosophy should make clear and delimit sharply the thoughts which otherwise are, as it were, opaque and blurred.

4.115 It will mean the unspeakable by clearly displaying the speakable.

4.116 Everything that can be thought at all can be thought clearly. Everything that can be said can be said clearly.

4.1212 What can be shown cannot be said.

4.123 A property is internal if it is unthinkable that its object does not possess it. (This blue colour and that stand in the internal relation of brighter and darker eo ipso. It is unthinkable that these two objects should not stand in this relation.)

5.122 If p follows from q, the sense of p is contained in that of q.

5.123 If a god creates a world in which certain propositions are true, he creates thereby also a world in which all propositions consequent on them are true. And similarly he could not create a world in which the proposition p is true without creating all its objects.

5.1361 The events of the future cannot be inferred from those of the present. Superstition is the belief in the causal nexus.

5.1362 The freedom of the will consists in the fact that future actions cannot be known now. We could only know them if causality were an inner necessity.

5.473 Logic must take care of itself. Everything which is possible in logic is also permitted. In a certain sense we cannot make mistakes in logic.

5.551 Our fundamental principle is that every question which can be decided at all by logic can be decided without further trouble. (And if we get into a situation where we need to answer such a problem by looking at the world, this shows that we are on a fundamentally wrong track.)

5.6 The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.

5.61 Logic fills the world: the limits of the world are also its limits. We cannot therefore say in logic: This and this there is in the world, that there is not.

For that would apparently presuppose that we exclude certain possibilities, and this cannot be the case since otherwise logic must get outside the limits of the world: that is, if it could consider these limits from the other side also. What we cannot think, that we cannot think: we cannot therefore say what we cannot think.

5.621 The world and life are one.

5.63 I am my world. (The microcosm.)

5.632 The subject does not belong to the world but it is a limit of the world.

5.634 This is connected with the fact that no part of our experience is also a priori. Everything we see could also be otherwise. Everything we can describe at all could also be otherwise. There is no order of things a priori.

6.1251 Hence there can never be surprises in logic.

6.13 Logic is not a theory but a reflexion of the world. Logic is transcendental.

6.361 In the terminology of Hertz we might say: Only uniform connexions are thinkable.

6.362 What can be described can happen too, and what is excluded by the law of causality cannot be described.

6.371 At the basis of the whole modern view of the world lies the illusion that the so-called laws of nature are the explanations of natural phenomena.

6.372 So people stop short at natural laws as at something unassailable, as did the ancients at God and Fate.

6.373 The world is independent of my will.

6.374 Even if everything we wished were to happen, this would only be, so to speak, a favour of fate, for there is no logical connexion between will and world, which would guarantee this, and the assumed physical connexion itself we could not again will.

6.3751 A particle cannot at the same time have two velocities, i.e. that at the same time it cannot be in two places, i.e. that particles in different places at the same time cannot be identical.

6.41 The sense of the world must lie outside the world. In the world everything is as it is and happens as it does happen. In it there is no value and if there were, it would be of no value. If there is a value which is of value, it must lie outside all happening and being-so. For all happening and being-so is accidental. What makes it non-accidental cannot lie in the world, for otherwise this would again be accidental. It must lie outside the world.

6.43 If good or bad willing changes the world, it can only change the limits of the world, not the facts; not the things that can be expressed in language. In brief, the world must thereby become quite another. It must so to speak wax or wane as a whole. The world of the happy is quite another than that of the unhappy.

6.431 As in death, too, the world does not change, but ceases.

6.4311 Death is not an event of life. Death is not lived through. If by eternity is understood not endless temporal duration but timelessness, then he lives eternally who lives in the present. Our life is endless in the way that our visual field is without limit.

6.4312 The temporal immortality of the soul of man, that is to say, its eternal survival also after death, is not only in no way guaranteed, but this assumption in the first place will not do for us what we always tried to make it do. Is a riddle solved by the fact that I survive for ever? Is this eternal life not as enigmatic as our present one? The solution of the riddle of life in space and time lies outside space and time. (It is not problems of natural science which have to be solved.)

6.432 How the world is, is completely indifferent for what is higher. God does not reveal himself in the world.

6.44 Not how the world is, is the mystical, but that it is.

6.45 The contemplation of the world sub specie aeterni is its contemplation as a limited whole. The feeling of the world as a limited whole is the mystical feeling.

6.5 For an answer which cannot be expressed the question too cannot be expressed. The riddle does not exist. If a question can be put at all, then it can also be answered.

6.52 We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have still not been touched at all. Of course there is then no question left, and just this is the answer.

6.521 The solution of the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of this problem.

6.522 There is indeed the inexpressible. This shows itself; it is the mystical.

6.53 The right method of philosophy would be this. To say nothing except what can be said, i.e. the propositions of natural science, i.e. something that has nothing to do with philosophy: and then always, when someone else wished to say something metaphysical, to demonstrate to him that he had given no meaning to certain signs in his propositions. This method would be unsatisfying to the other—he would not have the feeling that we were teaching him philosophy—but it would be the only strictly correct method.

6.54 My propositions are elucidatory in this way: he who understands me finally recognizes them when he has climbed out through them, on them, over them. (He must so to speak throw away the ladder, after he has climbed up on it.)

7 Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.